I’ll celebrate six years of sobriety this coming March.

I often say that the switch in my brain that should tell me when I’m sated (the one that helps other people stop after two drinks) is busted. Addiction isn’t fun. Or it seems fun, until it’s not. Once the negative consequences of my alcohol addiction started to outweigh the lie that I was just “having fun,” I decided to work very hard to relearn healthy coping skills through sobriety. One of those skills was choosing to abstain entirely from alcohol rather than to drink it in moderation. In my mind, I wouldn’t have to worry about my faulty “stop” switch if I never started in the first place.

This practice works well for me when it comes to not drinking or smoking cigarettes, but it’s not as easily applicable to other sneaky addictive behaviors…like work.

I investigated my own relationship with work in 2018, in my Week 23 post on Workaholic Tendencies. Yet, despite my commitment to building healthy work practices, I realized at the end of last year that I’d tipped back over into addictive work behaviors. My biggest red flag? I refused to take breaks. I felt like I “had” to keep working—even when I knew sitting for five hours straight would cause pain flare ups, even when I was hungry, or tired, or stressed out and past the point of diminishing returns.

Work Addiction and Graduate School

When I was a practicing alcoholic, I’d know when to stop drinking when I passed out. As a graduate student working on her dissertation primarily alone at home, I often don’t know when to stop until it’s too late and I’m reaching my hand up out of the waves of pain flare ups, stress, shame, and anxiety.

We need to take breaks. Grad students. Creatives. Entrepreneurs. Anyone working in the knowledge economy, working from home, and working on long term or large scale projects. But, if you’re a workaholic, taking breaks may feel counterintuitive or even downright dangerous and threatening.

Workaholism is often praised as “commitment” or “tenacity” or “passion” for one’s cause. Dr. Gabor Maté describes the confusion of passion with addiction well here:

Passions can be very consuming of time and energy, but they also feed your soul, your sense of being alive, your feeling of wholeness as a person. Addictions provide fleeting pleasure or gratification, but never leave you satisfied. And the same activity could be a passion for one person and an addiction for another. One might be a wine enthusiast, enjoying the refined pleasures the drink has to offer, while another person’s “love” for wine masks a fear of his own mind in its sober state.

Graduate students were likely used to receiving praise for our academic prowess and our commitment to our passions (AKA our research) when we were big fishes in small ponds of undergrad. Yet, in graduate school, that same academic prowess = the minimum requirements. Many humanities graduate students receive the message that the job market is horrible, so we feel a need to stand out among our peers–to do what is expected of us, and then to do more. (No wonder only 50% of doctoral students finished their degrees in 2013. I wonder what the statistic is now?)

I’ve said it before and won’t stop saying it until we create a better system: graduate school culture promotes workaholism. One way to challenge that system is taking breaks from our work.

So, How Do I Take Breaks?

Step 1: Recognize That Breaks Are Necessary

I love working. But I have a difficult time knowing when to stop, because my same “stop after two drinks” switch is faulty here: I do not naturally experience the satisfaction of being “done” with work. I have to learn how to recognize when I am done with work, and I can do this through and building new habits and using helpful tools.

If you’re an obliger like me, you might crave external accountability and guidelines for how to do a “good job.” Lacking explicit, external guidelines to tell you when to stop, you might continually work without taking breaks. If you struggle with workaholic tendencies, taking breaks is a practical way to manage the practice of tipping into overwork. Luckily, there are a number of tools that you can use to create external guidelines.

Step 2: Use Tools to Set Boundaries

Time management researcher Kevin Kruse recommends a “pulse and pause” method for taking breaks. This method suggests that we work for a predetermined period of time (pulse), then take an intentionally timed break (pause). A popular pulse and pause technique is the Pomodoro method, where you work for 25 minutes, take a break for five, and then take an an extended break after four sets of 25 on/5 off. Another seemingly random yet research-backed pulse and pause method is 52 minutes of working and then a 17 minutes break.

I love the pulse and pause technique because it provides external rules and trains me to step away from my work when a timer goes off. This lines up wonderfully with habit formation science, because it involves a cue, a routine, and a reward.

Step 3: Watch Out for Gray Areas

Marlee Grace writes about work gray areas in her brilliant book, How to Not Always Be Working: A Toolkit for Creativity and Radical Self-Care. She notes the tightrope we sometimes walk when our work and our hobbies overlap:

One of my favorite ways to take a break is stretching, light movement, and yoga. But, again, dancing and movement are in so, so many ways my work in this world. So here we are again, facing the deeply gray areas of the entire idea of this book.

But in terms of what feels like my career—writing books/teaching—I have found that movement without expectation (so not specifically tied to research and lesson planning) can be a freedom from working—working in the job sense, that is. (59-60)

If Grace’s work/break gray area is movement, mine is podcasts. When I’m not researching and writing for the blog or for my dissertation, I’m devouring creative entrepreneurial podcasts like Letters from a Hopeful Creative, Hashtag Authentic, Goal Digger, Raw Milk, and DIY Business Magic. They’re the kind of podcasts you want to be tuned into at all times, lest you miss a particular tip that will help you build a successful and meaningful business one day when you finally finish your PhD. Thus, while listening to them is very fun and invigorating, it is also work.

If listening to these podcasts is work, that means I am not truly taking a breaks when I listen to them.

I floated an idea to myself last week: what if I took a few days away from business podcasts and only listened to podcasts for explicit entertainment? Immediately, the fear in me bared her teeth: NO WAY. It felt like a punishment and made me panic…which made me curious, because I wondered what part of my work addiction I was triggering. I made a compromise with myself: what would happen if I took just two days away from listening to my business podcasts and instead listened to things purely for entertainment? I promised myself I could come back to my faves after the two days away, which calmed me down a bit.

I listened to the OnBeing interview with poet and philosopher David Whyte. It was beautiful. Krista Tippett’s interviews with poets blow me away. (Check out the John O’Donahue one for an exquisite treat). I listened to some of the Wait Wait Don’t Tell Me end of 2018 special. I listened to jazz. I laughed, I found myself daydreaming, remembering fond memories, and wondering things. I felt calm and warm and focused. I felt in a state of flow. When I listen to business podcasts, I do not daydream or wonder, because I am tuned in to learning and I don’t want to miss anything. When something is a gray area, like listening to business podcasts, researching for the blog, updating social media, or reading my dissertation research for “fun” (it is fun! but it’s also work!), I need to consciously value it as work, and I need to give myself some time off work, even the fun kinds.

Step 4: Limit Your Tech Use

I am also guilty of taking a “break” from one work task by working on a separate work task. Just as I consciously took a break from business podcasts, I also chose to take a break from checking my email and my social media during my breaks.

In my five and 15 minute breaks during my Pomodoro sessions, I would literally get up and walk into another room, do light stretches, drink a glass of water, or simply sit and practice mindful breathing for five minutes. This is the practice of relearning and building new habits.

If you want to take more intentional breaks from your own work, I’ve included some tools below that you can practice and hone for your own experience. They’re focused on helping you to shift your perspective around work and to help you strengthen your habits around healthy work practices.

Set Goals Intentionally

I mentioned the Rule of Three in 2.2: How to Use Lists to Tackle a Big Project. If you set three achievable goals for yourself at the beginning of your work session, you will be more likely to hit them and to feel like you have completed things (because, well, you have!). This practice can help you to recognize your accomplishments and to practice stepping away from your work even if you feel like there is still more to done on a larger project.

Not sure what to put on your Rule of Three list? Try out a Pomodoro (I use this free Tomato Timer website on my laptop).

Identify What Counts as a Break (and what doesn’t)

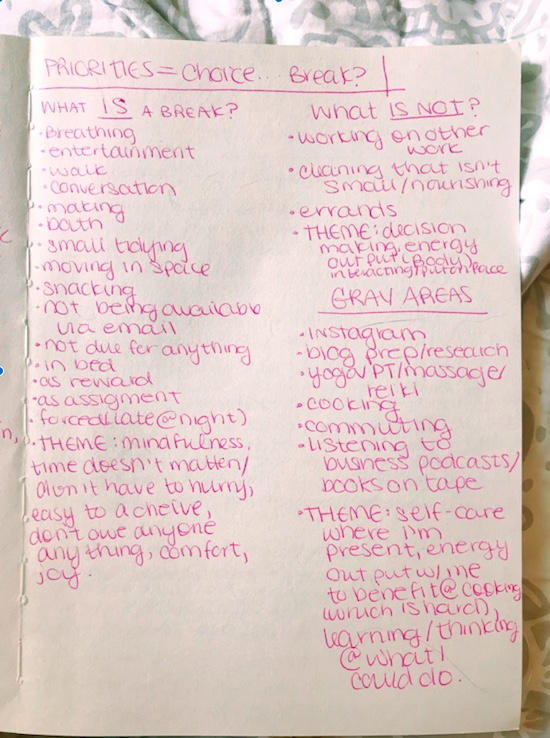

I was inspired by Marlee Grace’s discussion on gray areas to investigate what made my breaks feel refreshing or stressful. I answered the following questions by writing lists:

What IS a break?

What IS NOT a break?

What are my break gray areas?

Once I’d done this, I read over my answers for each question and identified themes for each list set so I would know what types of actions would constitute a refreshing break and what actions would cause stress and feed workaholism. You can see my answers below:

Learn to Listen to Your Body

Once you get in the practice of taking breaks, you will start finding natural places to take them. For example, while I was typing up my draft of this blog post I would take a break after I had drafted each of the Steps above. This helped me to clear my mind and refresh—I would get up and chat with my Sweetie (who was spending the day putting away the Christmas decorations—so we took a break together!) and drink water and move my body. When I was revising my post, I stopped to take a break whenever I started to clench my body or feel stressed.

I also attached an action to taking breaks: I literally will say out loud “I am taking a break,” which prompts me to shut my laptop and take some time away from work. Is the a statement or a mantra you can use to cue taking a break?

This blog is not affiliated with, associated with, or endorsed by the Pomodoro Technique® or Francesco Cirillo.

newsletter and free resources

Sign up below to access six free resources and my newsletter, tending.