If you follow The Tending Year on Instagram, you’ve like seen recent posts about spikes in my chronic pain.

Since I’m focusing on intention this month, I set an intention to investigate why my pain was spiking at night in an attempt to prevent, lessen, or accommodate my pain.

I realized something fascinating: when and how I spend my energy has a direct affect on my pain and my mood. This hearkens to the Spoon Theory, which I’ll break down for you after the jump. Also, I’m excited to share perhaps my most developed takeaway yet: an Energy Expenditure Survey & Plan that will guide you to evaluate and manage your own energy output!

What’s The Spoon Theory?

If you or someone in your circles has experienced chronic pain or illness, you may have heard about the Spoon Theory. Christine Miserandino developed this metaphor to explain the daily experience of having chronic illness to someone who does not share the same experience (see a PDF of the Spoon Theory here). By giving her “healthy” (her language) friend 12 spoons and taking away spoons to represent energy expenditure on tasks such as preparing for work, traveling, cooking, and dealing with emergencies, Miserandino “explained that the difference in being sick and being healthy is having to make choices or to consciously think about things when the rest of the world doesn’t have to.” The Spoon Theory thus serves as a metaphor to show that people expend energy differently.

Responses to The Spoon Theory

The Spoon Theory is a teaching tool, and as such can be both critiqued and altered by individuals to meet their interests and needs.

Adaptations of The Spoon Theory

Emily Davis of Chronically Healthy (an online community for people with invisible illnesses) writes in “Fork It; We’re Modifying The Spoon Theory” that “If you start the day with negative intention, already deciding before you get out of bed that it will be bad, then your day probably won’t be as good as it could have been.” She includes a great video in the linked article where she proposes that one should “Respect your limitations…but focus on your goals.”

Michelle L. adapts the Spoon Theory to what she calls a Cell Phone Theory in her article for The Mighty, “The Energy Metaphor I Find Easier to Explain Than the Spoon Theory.” She describes energy expenditure in terms of a faulty cell phone battery: no matter how much you charge it, it never quite gets to 100%. She hopes that her metaphor will encourage people to see the difference between the experience of people with a battery that can charge to 100% (or people who do not have chronic pain or illness) and people whose battery cannot work the same way. Her critique is as follows:

“There are always those people who insist that, even though they’re not ill, they count spoons (or battery percentages). There’s only so many hours in a day and so much energy, after all. Since everyone has experienced a tech glitch – or running low on flatware – it’s sometimes difficult to make someone understand that this is different. This is constant, and there’s no replacing the phone.”

A Critique of The Spoon Theory

The author of the blog It Was Lupus offers a critique of the Spoon Theory here. She critiques both Miserandino’s Theory as well as she she calls “the whole “But you don’t look sick” trademark[, which] is based on the idea that we need everyone to know we have Lupus so that they can treat us differently, give us more leeway and essentially feel bad for us.” Just as people both praise and challenge the Spoon Theory, readers both praised and challenged It Was Lupus’s critique. I think that serves is a good reminder that everyone experiences chronic pain or chronic illness differently.

Kate’s Take on The Spoon Theory

I think the Spoon Theory is a great teaching tool to educate people about chronic pain or chronic illness if they are are new to the topic. I also think it should not be used as a strict rule and that it should be open to change and context.

I’ll use myself as an example. As you’ll see in my takeaway examples, after inventorying my own energy expenditure, I realized that chores like cooking, cleaning, doing laundry, grocery shopping, and changing my bed sheets are exhausting when I do them (1) at night, and (2) when my pain is high. For that reason, I really related to Miserandino’s description to her friend about choosing how to spend energy at the end of the day:

“When we got to the end of her pretend day, she said she was hungry. I summarized that she had to eat dinner but she only had one spoon left. If she cooked, she wouldn’t have enough energy to clean the pots. If she went out for dinner, she might be too tired to drive home safely. Then I also explained, that I didn’t even bother to add into this game, that she was so nauseous, that cooking was probably out of the question anyway. So she decided to make soup, it was easy. I then said it is only 7pm, you have the rest of the night but maybe end up with one spoon, so you can do something fun, or clean your apartment, or do chores, but you can’t do it all.”

If my pain is really high, crawling across my bed to tuck in a fitted sheet might strain my muscles and pull on my tailbone. But, if I change my sheets in the morning, when my pain is usually very low or nonexistent, my muscles will be more relaxed and the task will be quite painless. Thus, changing sheets doesn’t always use the same amount of energy. Similarly, certain tasks that might be out of the question for me when I’m tired and in pain (cooking a meal or doing laundry) are doable if I have a friend there to help me. Sometimes I choose to do certain tasks when I have pain, and sometimes I choose not to. Sometimes a task requires me to spend spoons, and sometimes that same task takes very little energy. Thus, for me, the Spoon Theory is contextual.

I’ll break down my Energy Expenditure Survey & Plan below, but I’ve also generated a version of the survey in GoogleSheets that you can access here. Just copy and paste the content to a new Excel or GoogleSheets document and edit the details to reflect your experiences! Note: This is a multi-step exercise, so give yourself adequate time for each step. You could even break it down across three different sessions, or do it with a friend and share your answers when you complete each section.

Step 1: List Your Energy Expenditure Tasks

You’d be surprised with just how many things you do in just ONE day! This Step asks you to make an inventory of them all.

To start, you will create a list down the left side of a piece of paper or in the left column of an Excel sheet. List all of the tasks that you do regularly that you would count as expending energy—this might include tasks like work errands and cleaning the litter box, but don’t ignore self care tasks like doing your nails or self maintenance tasks like making your bed if they feel like energy expenditures for you! If you’re not sure if something is an energy expenditure, put it on there for now and you can always take it off later. I know that something is definitely an energy expenditure if I find it difficult to do when I’m experiencing pain or when I’m tired.

I recommend putting your tasks in categories, as I did below (I also had a section for blog, appointments, and miscellaneous, but you might have things like childcare, etc.):

EMPLOYMENT

Work in Physical Office

Work Errands

Work Meetings

Work Content Development

Work Communication

DISSERTATION

Diss. Meeting

Diss. Reading/Research

Diss. Content Development

Diss. Communication

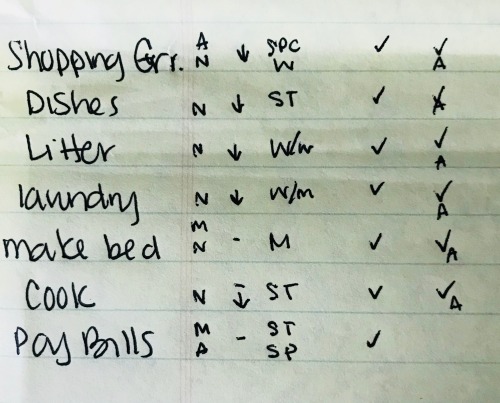

ERRANDS/HOME

Shopping

Dishes

Kitty Litter

Laundry

Change Bed sheets

Cook

Pay Bills

Step 2: Questions About Each Expenditure Task

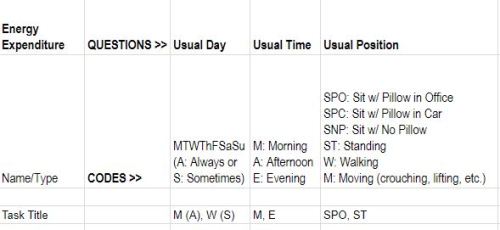

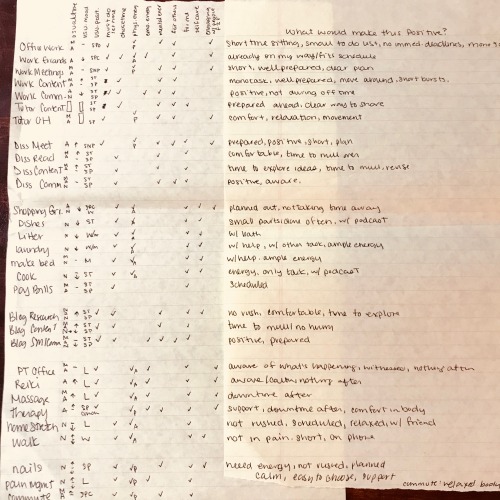

Now that you have inventoried the tasks that you spend your energy on, you will ask questions about how each of those tasks fits into your life. Type these questions across the top row of your document or hand write them at the top of the page. Also write or type codes for how you might answer those questions. If you like, you can adapt my questions and codes to your fit your own experiences.

Here is an example from my Energy Expenditure Survey & Plan that shows how I formatted my questions and codes in rows 2 and 3 to the right of the the list I made in Step 1:

You can use my questions and codes as a guide, but you should update them for your own experiences:

- Usual Day: MTWThFSaSu (A: Always or S: Sometimes)

- Usual Time: M: Morning; A: Afternoon; E: Evening

- Usual Position: SPO: Sit w/ Pillow in Office; SPC: Sit w/ Pillow in Car; SNP: Sit w/ No Pillow; ST: Standing; W: Walking; M: Moving (crouching, lifting, etc.)

- Must Do at Set Time or I Choose Time?: ST: Set Time; ICT: I Choose Time

- Type of Energy: AP: Active Physical; PP: Passive Physical (i.e., sitting that causes pain); E: Emotional; M: Mental

- What Type of Emotional Energy if in Pain?: Sa: Sadness; St: Stress; An: Anger; STF: Struggle to Focus

- For Others or For Me?: FO: For Others; FMM: For Me Maintenance; FMSC: For Me Self Care

- Alone or Engage w/ Others (Digital or Face to Face): A: Alone; OD: Engage w/ others, Digital Communication; OF2F: Engage w/ Others, Face to Face

Finally, you should answer the following question for each energy expenditure task: What would be my ideal experience with this task? (Another way to think of this question is “How could I make this experience more positive?”) You could skip this task, but I liked ending the survey section on a positive note.

My first draft of Step 1 and Step 2 ended up looking like this (I later typed it up so I could align my checkmarks with my codes):

Step 3: Make A Practical Energy Expenditure Plan

Once you’ve filled out your survey, give it a good read over to see where you want to plan, adjust, or accommodate. See below for my process and feel free to use it as a model to make explicit changes by filling in the blanks for: “I noted that ___,” “I realized that ____,” and “With this awareness, I choose to ____.”

I noted that… my Errands/Home section had some very interesting things happening…

- the most downward facing arrows in the “Usual Mood” section

- the most “Physical Energy” expenditure outside of doctor’s appointments

- the most “For Me Self Maintenance”

- and these tasks almost all happened at night.

I realized that… I know that my pain is usually higher at night, so it makes sense that physical tasks would be harder to accomplish then, but I hadn’t realized that I had been sacrificing my self maintenance by trying to do it through pain. No wonder I was so sad and stressed out at night, and no wonder I dreaded things like cooking and cleaning!

With this awareness, I chose to… set practical rules that might help me to have a better experience with home/errands. These included:

- Stop working at 5pm: After 5pm, only spend time with friends, take baths, read, and otherwise relax. “Work” in this case included things like doing my nails, a task that I greatly enjoy but which usually takes me 1-2 hours and requires me to sit.

- Plan dinners ahead of time: Take time during the day to shop for easy ingredients that I can throw together and don’t mind eating over and over, like salads.

- Spread errands/home tasks throughout the day and week: If I use a dish during the day, try to wash it soon after; if I see something out of place when I’m getting ready for work in the morning, put it away where it goes.

- Plan for help: Bring laundry to Sweetie’s house to ask her to help with with on the weekend.

*Please note that the original version of this blog post was published here.

newsletter and free resources

Sign up below to access six free resources and my newsletter, tending.