Way back when I was an English major in undergrad, I waited until my very last semester to satisfy my math requirement via a freshman-level “Intro to Logic” class.

Although I anticipated that learning math (or was it philosophy?) would be a total snorefest, I found myself fascinated by the ways that symbols stood in for words and showed the complex interactions between concepts.

Looking back, I’m actually not surprised that I was so jazzed about introductory logic formulas. Whenever I’m writing—an analysis, a journal article, a lesson plan, and now, a whole damn dissertation—I do what I call “turning writing into a math problem.” If I use a formula like “A + B = C, except in the case of D, in which case E” to organize my thoughts, my writing is more structurally sound.

It turns out that fun method I called “turning writing into a math problem” already has a name: concept mapping.

Once I knew that “writing like math” was actually concept mapping, I researched how to do it more efficiently, and I learned that it’s a more complex version of mind mapping. I’ve converted my findings into this “how to” post for you, complete with practical tips you can apply to your own thinking, planning, or writing.

If you’re a grad student or scholar who is tackling a big writing project, I hope you’ll find some helpful tips here that you can adapt to your own process. Even if you’re not writing a dissertation or article, you should still read after the jump because mapping can be used for just about any organizing or planning activity.

The Difference Between Mind & Concept Mapping

Mind Mapping

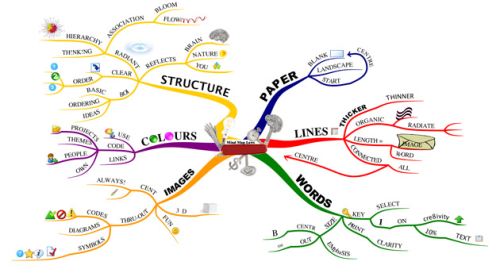

Developed in the 1960s by Tony Buzan, mind mapping is method for organizing information visually in “a simple hierarchical radial diagram.” Here’s a mind map by Buzan about mind mapping, so you can see what it looks like:

(Image: “Mindmap”)

By writing (or drawing) an idea in the center and using different colors to attach related ideas via branches, we’re able to organize ideas in a way that engages the left and right hemispheres of the brain—something that writing a plain ol’ list doesn’t do.

Why does it matter that we’re engaging our whole brain? Check out this description from Academic Ladder:

The brain is an associative network, and the right hemisphere (in most people) is responsible for non-verbal, visual, associative and much creative thinking. Normally when writing, we are mostly making use of our left hemisphere, which tends towards the analytical, one-thought-at-a-time approach. Our internal thoughts, however, are not shaped like that. Thus we have a roadblock as we try to get our brilliant thoughts on paper.

By using a Mind Map as a starting point for thinking, you can bypass the blockage and feeling of overwhelm caused by overly analytical thinking. The Mind Map allows you to see more than one thought at a glance, and in doing so helps clarify your thinking. It shows the way ideas are interrelated (or less related than you thought.) It allows more access to creative, non-linear parts of your brain.”

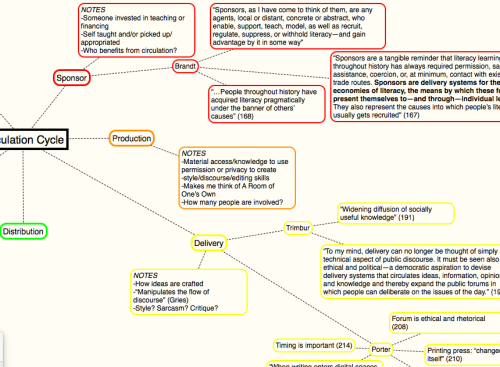

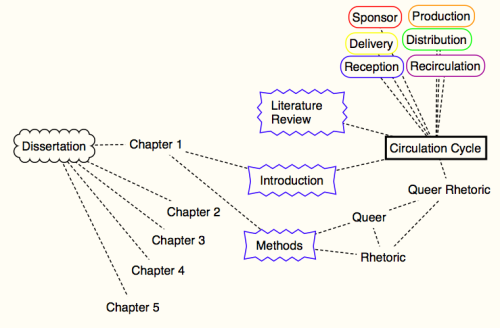

People tend to use mind mapping to brainstorm and take notes, but you can also use it to budget, write a to do list, or any other generative activity. Here’s a snippet of a mind map I made last week about the Circulation Cycle:

Concept Mapping

Mind mapping and concept mapping are sometimes used interchangeably, but concept mapping is actually more complex.

When you mind map, you branch out from one central idea—you still show a hierarchy of ideas, but they always relate back to the central idea.

When you concept map, you show the complex relationships between and across concepts, which expands beyond a simple hierarchy.

Why Concept Mapping Works for Writing

One of the best things I read in my mapping research last week was a series of dissertation writing tips by artist and multimedia designer, Dr. Yago De Quay. You can check out his post on mind maps here, his post on building conceptual maps here, and his post on building propositions here, but I’ll point to some key parts here.

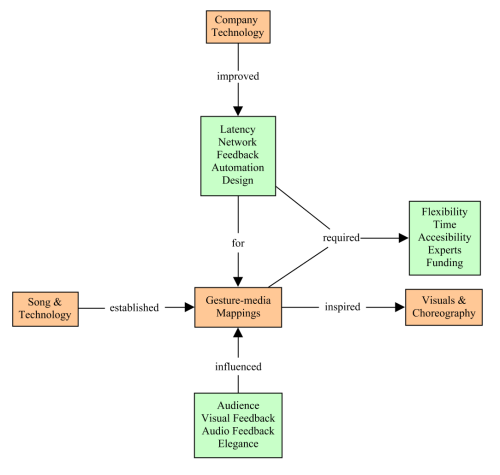

We can beef up our concept maps via mathematical tools called proportions that define the relationship between two ideas by showing how ideas affect or are affected by one another. Check out the proportions (the words that connect the boxes) in this image from Dr. De Quay’s research:

(Image: “From Conceptual Map to theory”)

I don’t know about you, but when I look at the image above, I see a paragraph. The words “improved,” “for,” “required,” etc. are proportions, and they show the relationships between the key nouns and concepts. Throw in a few transitional phrases and some sign posting language to organize the sentences, and you’ve got yourself a basic framework for actually writing your concepts in full sentence format.

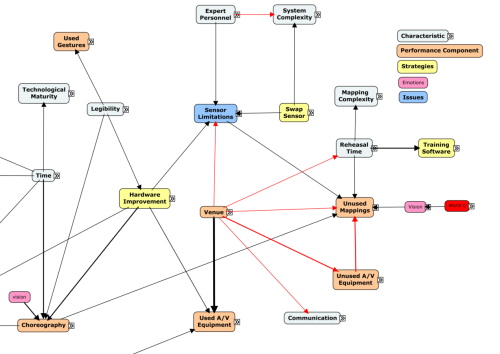

If your nerd mouth is watering at this style of “writing like math” (or is it mathing like writing?), you should definitely check out Dr. De Quay’s post on concept maps to see how he uses arrows during his coding process to show the way concepts influence one another. Here’s an example to whet your appetite:

(Image: “Conceptual Map of Ad Mortuos”)

Digital Versus Hand Written

Digital and hand written mapping both have their places. I usually mind map by hand, but for the sake of this post I tried using a few digital mapping programs that were recommended as favorites in some of the research I found. My personal favorite was Scapple, which was developed by the same people who made Scrivener (an app I already use for writing projects). Scapple lets you save and print your maps, and they offer a free 30 day trial where they only count the days when you actually use the program. I think you may be able to actually drag your maps into Scrivener in the paid version, but I haven’t gotten that far in my tinkering in the trial version. (PS: I think I will probably buy Scapple when my free trial runs out, so I’ll report back on the diff between trial/paid one day.)

Pros of Digital Mapping

When I mapped my dissertation outline in Scapple, I started by just writing up my key words in individual note bubbles and then later connected them as I saw they fit. I could change the shape/size/color of my notes and connect them to multiple notes, which was nice for visualizing how concepts related to one another. I also liked that I could move things around if I changed my mind and that I could have multiple maps happening on one screen.

Here’s a quick sample of my early dissertation mapping in Scapple:

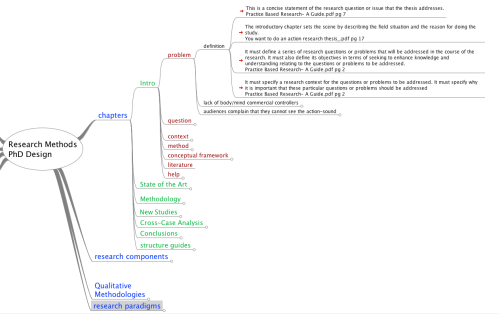

Here’s a picture of Dr. De Quay’s dissertation mapping, which I think he made via the program FreeMind:

(Image: “Mind Map”)

Digital Mapping Options

Interested in trying out digital mapping, but not sure which app to us? Check out Lifehack’s “11 Free Mind Mapping Applications & Web Services” for a review of a bunch of them. As I said above, I really liked Scapple because of the way I could move things all over the page, but you might prefer another.

Use Mapping For Knowledge Management

The productivity company Asian Efficiency has a cool list of “10 Ways to Use Mind Maps Over Text Notes,” including the brilliant idea to use maps for knowledge management, AKA keeping track of your resources. Check out their example of their map below, where they organized and linked to particular documents.

(Image: “Knowledge Mgmt Example”)

Mapping for Teachers

I found a number of resources that broke down mapping into teachable lessons, including Creativity & Productivity Blog Focus’s “Mind Maps for Essay Writing (Guide + Examples)” and “The Student’s Guide to Mind Mapping,” and this mind mapping lesson plan by the Institution for Teaching & Learning.

Mapping for Dissertators

If you’re interested in applying mapping to your dissertation process, you should check out these resources:

- Dr. Marialuisa Aliotta’s “How to Structure Your Chapters in 3 Quick Steps”

- Mary Barone Martin’s “Mind Maps for Conceptual Understanding: A Preliminary Report”

- The Dissertation Mind Map

- Academic Ladder’s “Mind Map and Write Your Dissertation or Publish”

*Please note that the original version of this blog post was published here.

Newsletter

Sign up below to access my free newsletter, Tending with Dr. Kate Henry.